.JPG)

Cyrus the Great (

کوروش بزرگ) (c. 600 BC or 576 BC–530 BC) was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. The son of Cambyses I (

کمبوجيه), he originated from Persis, roughly corresponding to the modern Iranian province of Fars. Under his rule, the empire embraced all the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East, expanded vastly and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much of Central Asia and the Caucasus. From the Mediterranean Sea and Hellespont in the west to the northwestern areas of India, Cyrus the Great created the largest empire the world had yet seen. Superimposed on modern borders, the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus' rule extended approximately from Turkey, Israel, and Armenia in the west to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and to the Indus River in the east. He pronounced what some consider to be one of the first historically important declarations of human rights via the Cyrus Cylinder sometime between 539 and 530 BC.

According to the ancient historians, Astyages, father of Mandana and Cyrus’s grandfather, was told in a dream that his grandson would overthrow him. To avoid this he ordered that the baby be killed. However the official delegated with the task gave the baby to a shepherd instead. When Cyrus was ten years old, the deception was discovered by Astyages as the behavior of Cyrus was too noble. Because of the boy's outstanding qualities Astyages allowed him to return to his biological parents, Cambyses I and Mandana.

Cyrus the Great had a wife named Cassandane. She was an Achaemenian and daughter of Pharnaspes. From this marriage, Cyrus had four children: Cambyses II (who would later become the king of Persia), Bardia, Atosa (who would marry Darius the Great), and another daughter whose name is not attested in the ancient sources.

.JPG)

The reign of Cyrus the Great lasted between 29 and 31 years. Cyrus built his empire by conquering first the Median Empire, then the Lydian Empire and eventually the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Either before or after Babylon, he led an expedition into central Asia, which resulted in major campaigns that were described as having brought "into subjection every nation without exception". Cyrus did not venture into Egypt, as he himself died in battle, fighting the Massagetae along the Syr Darya in December 530 BC. He was succeeded by his son, Cambyses II, who managed to add to the empire by conquering Egypt, Nubia, and Cyrenaica during his short rule.

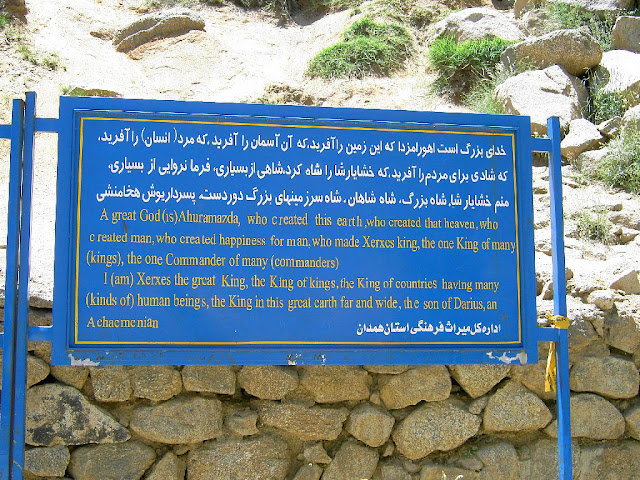

Cyrus the Great respected the customs and religions of the lands he conquered. It is said that in universal history, the role of the Achaemenid Empire founded by Cyrus lies in its very successful model for centralized administration and establishing a government working to the advantage and profit of its subjects. In fact, the administration of the empire through satraps and the vital principle of forming a government at Pasargadae were the works of Cyrus. Cyrus created the first postal system in the world, and this must have helped with intra-Empire communications. He is also well recognized for his achievements in human rights, politics, and military strategy, as well as his influence on both Eastern and Western civilizations.

Though it is generally believed that Zoroaster's teachings exerted an influence on Cyrus's acts and policies, no clear evidence has been found that indicates that Cyrus practiced a specific religion. His liberal and tolerant views towards other religions have made some scholars consider Cyrus a Zoroastrian king. Proponents of this belief point out that fire altars and the mausoleum at Pasargadae demonstrate Zoroastrian practices, and cite Greek texts as evidence that Zoroastrian priests held positions of authority at Cyrus's court. On the other hand other scholars emphasize the fact that Cyrus is known only to have honored non-Zoroastrian gods. Cyrus initiated a general policy of religious tolerance throughout his vast empire.

Though his father died in 551 BC, Cyrus the Great had already succeeded to the throne and became king of Anshan in 559 BC; however, he was not yet an independent ruler. Like his predecessors, Cyrus had to recognize Median overlordship. The province of ancient Persis declared its independence and commenced its revolution as it attempted to separate from the Median Empire as Cyrus rallied the Persian people to revolt against their feudal lords, the Medes. In 552BC, he lead his armies against the Medes until the capture of Ecbatana in 549 BC, effectively conquering the Median Empire and assuming the title King of Persia.

The exact dates of his Lydian conquest are unknown, but it must have taken place between Cyrus's overthrow of the Median Empire and his conquest of Babylon (539 BC). Lead by Croesus, the Lydians first attacked the Achaemenid Empire's city of Pteria. Cyrus levied an army and marched against the Lydians, increasing his numbers while passing through nations in his way. The Battle of Pteria was effectively a stalemate, with both sides suffering heavy casualties by nightfall. While Croesus awaited reinforcements via his allies, Cyrus pushed the war into Lydian territory and besieged Croesus in his capital, Sardis. Cyrus defeated and captured Croesus and occupied the capital at Sardis, conquering the Lydian Kingdom in 546 BC.

By the year 540 BC, Cyrus captured Elam and its capital, Susa. Cyrus fought the Battle of Opis in or near the strategic riverside city of Opis on the Tigris, north of Babylon. The Babylonian army was routed, and Sippar was seized without a battle, with little to no resistance from the populace. It is probable that Cyrus engaged in negotiations with the Babylonian generals to obtain a compromise on their part and therefore avoid an armed confrontation. Two days later, his troops entered Babylon, again without any resistance from the Babylonian armies. To accomplish this feat, the Persians, using a basin dug earlier by the Babylonian queen Nitokris to protect Babylon against Median attacks, diverted the Euphrates river into a canal so that the water level dropped "to the height of the middle of a man's thigh", which allowed the invading forces to march directly through the river bed to enter at night. Prior to Cyrus's invasion of Babylon, the Neo-Babylonian Empire had conquered many kingdoms. In addition to Babylonia itself, Cyrus probably incorporated its subnational entities into his Empire, including Syria, Judea, and Arabia Petraea, although there is no direct evidence of this fact. After taking Babylon, Cyrus the Great proclaimed himself "king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four corners of the world".

When Cyrus conquered Babylon, he declared the first Charter of Human Rights known to mankind. There he was much admired by the Jews, allowing more than 40,000 Jews who had been held captive since the time of Nebuchadnezzar to leave Babylon and return to their homeland. One of the few surviving sources of information that can be dated directly to Cyrus's time is the Cyrus Cylinder, a document in the form of a clay cylinder inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform. It had been placed in the foundations of the Esagila (the temple of Marduk in Babylon) as a foundation deposit following the Persian conquest in 539 BC. It was discovered in 1879 and is kept today in the British Museum in London. The text of the Cylinder denounces the deposed Babylonian king Nabonidus as impious and portrays Cyrus as pleasing to the chief god Marduk. It goes on to describe how Cyrus had improved the lives of the citizens of Babylonia, repatriated displaced peoples and restored temples and cult sanctuaries. The United Nations has declared the relic to be an "ancient declaration of human rights" since 1971, approved by then Secretary General Mr. Sithu U Thant. The Cyrus Cylinder has become part of Iran's cultural identity.

The details of Cyrus's death vary by account although one of the more popular states that Cyrus met his fate in a fierce battle with the Massagetae, a tribe from the southern deserts of Khwarezm and Kyzyl Kum in the southernmost portion of the steppe regions of modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, following the advice of Croesus to attack them in their own territory. In order to acquire her realm, Cyrus first sent an offer of marriage to their ruler, Tomyris, a proposal she rejected. He then commenced his attempt to take Massagetae territory by force, beginning by building bridges and towered war boats along his side of the river Jaxartes, or Syr Darya, which separated them. Tomyris then challenged Cyrus to meet her forces in honorable warfare, inviting him to a location in her country a day's march from the river, where their two armies would formally engage each other. He accepted her offer, but, learning that the Massagetae were unfamiliar with wine and its intoxicating effects, he set up and then left camp with plenty of it behind, taking his best soldiers with him and leaving the least capable ones. Lead by the general of Tomyris's army Spargapises, who was also her son, the Massagetian troops killed the group Cyrus had left there and, finding the camp well stocked with food and wine, unwittingly drank themselves into inebriation, diminishing their capability to defend themselves, when they were then overtaken by a surprise attack. They were successfully defeated and, although he was taken prisoner, Spargapises committed suicide once he regained sobriety. Upon learning of what had transpired, Tomyris denounced Cyrus's tactics as underhanded and swore vengeance, leading a second wave of troops into battle herself. Cyrus the Great was ultimately killed, and his forces suffered massive casualties in what Herodotus referred to as the fiercest battle of his career and the ancient world. When it was over, Tomyris ordered the body of Cyrus brought to her, then decapitated him and dipped his head in a vessel of blood in a symbolic gesture of revenge for his bloodlust and the death of her son. Upon Cyrus's death, his son Cambyses II succeeded him. He attacked the Massagetae and recovered Cyrus's ravaged body.

Other accounts claim that Cyrus met his death while putting down resistance from the Derbices infantry, a Central Asian tribe. They were aided by other Scythian archers and cavalry, plus Indians and their elephants. Supposedly it was an Indian spear that wounded Cyrus, who died several days later northeast of the headwaters of the Sry Darya. An alternative account further claims that Cyrus died peaceably at his capital.

Cyrus's remains were interred in his capital city of Pasargadae, where today

a limestone tomb still exists. The inscription on his tombstone reads: “O man, whoever you are and wherever you come from, for I know you will come, I am Cyrus who won the Persians their empire. Do not therefore begrudge me this bit of earth that covers my bones.”

In 1994, a replica of a bas relief depicting Cyrus the Great was erected in a park in Sydney, Australia. It is intended as a symbol for multiculturalism, and to express the coexistence and peaceful cohabitation of people from different cultures and backgrounds. October 29th, the day that Cyrus the Great entered Babylon, has been designated as Cyrus the Great Day.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)

%20-%20Tajikestan.jpg)

%20-%20Khomeini%20Square%20Arak.jpg)

%20-%20Darolfonoon%20Tehran.jpg)